Did humans hasten the extinction of the woolly mammoth?

Oftentimes, studies on the extinction of a species focus on reconstructing the events that transpired when the last remaining population/individual was alive. The new study notes that this is a truncated view, as “pathways to extinction start long before the death of the last individual.” These pathways and processes can commence as early as millennia before the final extinction event.

Using counterfactual scenarios, we show that in the absence of humans, woolly mammoths would have been more abundant across time and would have persisted for much longer, perhaps even avoiding extinction in climatic refugia https://t.co/dgUWG4ogEM pic.twitter.com/1JPv5GvvuX

— David Nogues-Bravo (@Noguesbravo) November 9, 2021

The study approached the vexed question of the interactions between humans and mammoths using two models.

*First, they juxtaposed the fossil record – that included the location and date of each fossil specimen – with established palaeoclimate models over the last 21,000 years.

*Second, a genetic model of the global diaspora of anatomically modern humans over the last 125 thousand years was considered (Homo sapiens originated ~30000 years ago).

Finally, these were taken together to understand how humans influenced some key ecological processes of extinction: niche lability, dispersal, population growth, and the Allee effect. Niche lability refers to a phenomenon whereby a species or a population does not retain its niche in order to preserve its ecological traits through space and time, and the Allee effect refers to a phenomenon wherein lower per capita birth rates lead to a loss in genetic diversity.

The range of the woolly mammoth contracted in North-East Europe around 19,000 years ago and the species was completely wiped out in most of Europe in the next 5,000 years. There were, however, certain areas called ‘refugia’ ( patches of tundra ecosystem remained amidst a drying climate) where the mammoth did survive: areas that are now Britain, Northern France, Belgium, and some areas of Netherlands and Denmark.

The models imply that the populations of the woolly mammoth would have remained in the Arctic refugia as late as the mid-Holocene, nearly 5,000 years longer than what had been earlier determined through fossil evidence. The Holocene period about 10,000 years ago is a time most notably marked by a transition from hunting-gathering to settled agriculture in human history.

The warming up of the climate around 17,500 years ago separated the populations of humans and mammoths. While humans populated the areas that were left open to colonisation by the retreating ice sheets, mammoths further retreated to the tundra pockets where they could survive.

The authors highlight that the interplay between mammoths-climate-humans was not homogeneous over space and time and that these ‘spatiotemporal heterogeneities’ played a key role in the final extinction event.

The study further asserts that the ‘dynamics of these extinction determinants were labile’. For example, in Northern Fennoscandia (the region that covers Scandinavian countries along with a part of Russia) the existing mammoth populations experienced a far greater threat from the warming of the climate in the Holocene than from humans. This is not the case for populations in Asia and Beringia, where the mammoth’s extirpation “closely mirrored the pattern of continent-wide extinctions observed for Eurasia, with humans having a proportionately larger threatening influence on expected minimum abundance.”

Nonetheless, the models generated by the study show that had humans been absent altogether, mammoths “would have persisted for much longer, perhaps even avoiding extinction within climatic refugia.”

The models showed that the absence of humans registered a “24 per cent increase in their persistence beyond 3800 years ago.”

Associate Professor David Nogues-Bravo from the University of Copenhagen and co-author of the study explains in a release: “Our analyses strengthen and better resolves the case for human impacts as a driver of population declines and range collapses of megafauna in Eurasia during the late Pleistocene…It also refutes a prevalent theory that climate change alone decimated woolly mammoth populations and that the role of humans was limited to hunters delivering the coup de grâce. And shows that species extinctions are usually the result of complex interactions between threatening processes.”

– The author is a freelance science communicator. (mail[at]ritvikc[dot]com)

East Europe Ka Ranveer Allahbadia … and other memes go viral after Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky’s public spat

East Europe Ka Ranveer Allahbadia … and other memes go viral after Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelensky’s public spat  Allegro Makes $1 Billion East Europe Expansion to Rebuff Amazon

Allegro Makes $1 Billion East Europe Expansion to Rebuff Amazon  Bulgaria | OECD

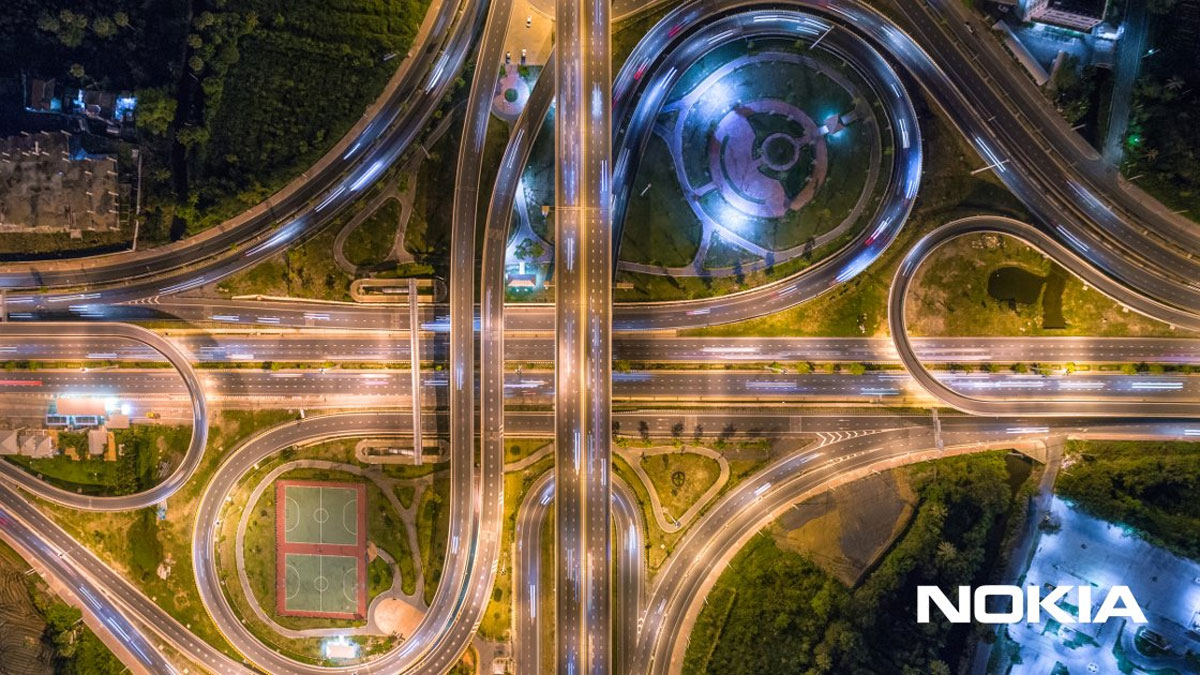

Bulgaria | OECD  Nokia and UG to Deploy Fibre Services Across South East Europe

Nokia and UG to Deploy Fibre Services Across South East Europe  More trains between Northern and South-East Europe for Hupac

More trains between Northern and South-East Europe for Hupac